Shelia Ross, D.N.P., thinks that getting patients the right stroke treatment more quickly starts in the community. See why.

Time is brain.

That sentiment isn’t novel in healthcare. It’s something that’s widely known and has been for a while.

As the stroke certification coordinator at USA Health, Shelia Ross, D.N.P., knows it too. That’s why her job is to make sure that all the protocols, all the systems, all the coordination is in place to ensure that the stroke patients—and potential stroke patients—who are wheeled through the doors of University Hospital receive care that’s equal to or better than the national standards set forth by the American Heart Association and the Joint Commission.

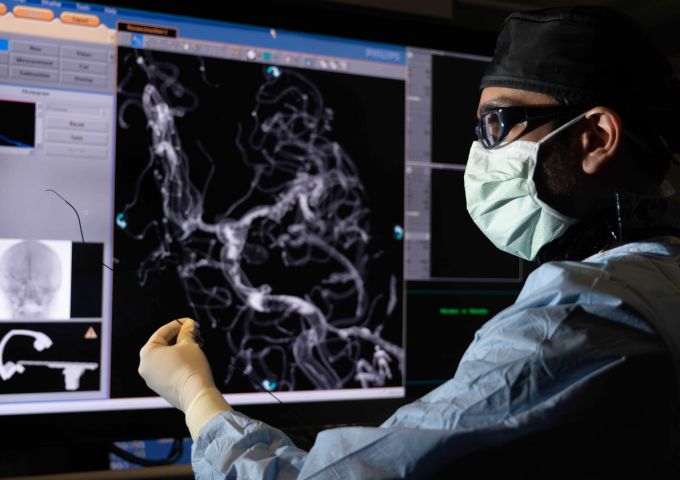

Nobody at USA Health waits for the patient to arrive before the preparation begins. A team of nearly a dozen health professionals—residents, an emergency department physician and charge nurse, neurology faculty and a pharmacist if needed—all gather to meet the patient at the door. The arrival of the patient triggers a burst of activity that may involve a combination of observation, evaluation, a CT scan, administration of tPA (the clot-busting medication), preparation for interventional radiology and other treatments. While it might be dizzying to behold, it’s actually a well-defined, data-driven process that has garnered USA Health national recognition annually for the stroke care provided.

But at an academic health center like USA Health, caregivers are always looking for new ways to provide an even higher level of care. And that search has led Ross and others out into the community to spearhead stroke education efforts.

“We don’t miss an opportunity,” Ross says. “If we get asked, someone is going to go and talk and educate the community on the signs and symptoms of stroke—the importance of time.”

As a result, people both inside the health system and out in the community now recognize the signs and symptoms of a stroke more quickly. The number of stroke codes the emergency department encounters has tripled, which is a good thing. It means that more people are learning about strokes and paying attention to what’s happening to those around them.

“If we can touch one person in a group of 50,” Ross added, “it’s worth it to me.”

That’s what it means to see things differently, which is one of the ways we’re transforming medicine.